A gentle light diffused my parents’ bedroom. Perhaps it was the day I was born. I just remember feeling peaceful, secure, and contented.

* * *

My name is Jo Johnson. Full name, Peter Joseph Johnson, after my two grandfathers, but I’ve always been called Jo.

I was born in the front bedroom of the ground-floor flat at 19 Bentinck Street, Greenock, on 25th February 1957.

19 Bentinck Street, Greenock.

I was the first of five children, four boys and a girl, born to Mum and Dad between 1957 and 1963. In order of birth, my siblings are James, William, John and Elisabeth. Mercifully, perhaps, most of my earliest memories have disappeared into the mists of time. Only a few snapshots remain—some are actual photographs taken by Mum or Dad, others are memories, imprinted with greater or lesser detail on my mind.

* * *

Dad and Mum on Octavia Terrace. I’m in the driving seat, James facing Dad and Mum, baby William inside pram.

Mum’s father, Peter Christison, came to live with us for two or three years before he died. Until he retired, he was the Head Gardener at Milton Lockhart estate in the Clyde Valley. We called him Grandad. I remember him sitting on the sandstone wall outside the house, dabbing the end of a dandelion stalk on his tongue. He liked the bitter taste and used it as an herbal aid to health. Another time, he was eating an apple. When I imitated the way he munched it, he laughed and exaggerated the munching for my entertainment. Mum told me he wanted to see me going to school before he died. He got his wish.

Grandad, keeping an eye on me and James in the pram

Mum and Dad also brought Grandad’s sister (Mum’s Aunt Mary), to stay with us when she could no longer look after herself. I only ever remember her lying in bed—but she was always pleased to see us children when we ventured into her room.

Dad was teaching Maths at the Mount School at the time but had rented a shop in Cathcart Street, which he stocked with drapery goods and children’s clothes. He employed a girl to work in it during the day. Grandad was so keen to see Dad’s new venture, he walked all the way from Bentinck Street to the shop and back again. Mum said it was too much for him. She thought the extra effort had damaged his heart. He became ill and was confined to bed. Whenever he wanted anything, he took his knobbly brown walking stick, whacked the end of the bed and shouted “Jean!—Jean!” Eventually it was too much for Mum to look after him. An ambulance arrived and took him to Larkfield Hospital where he died of heart failure some weeks later. He told Mum his heart was ‘done’. She visited him a day or two before he died and said, “If it’s the Lord’s will Dad, you’ll get better.” He knew different and said sharply, “Jean! Speak the truth!”

As a Christian, Grandad was a conscientious objector during the first World War. When he stood before the tribunal, the judge said, “What would you do if the Germans came and started killing your family?” He answered: “It would be a quick despatch to glory.” The judge gave him work of National Importance in Forestry.

At one of our Bible conferences, some young people were sitting in front of Grandad, giggling and laughing. He leaned forward and said, “There’ll be nae laughin’ in hell.”

Harry King told me that Grandad had some memorable turns of phrase when he prayed, such as “We lift our hearts to Thee as a flower lifts its face to the sun.”

Dad related a story Grandad told him, about a carter pulling a heavy load of hay up the Lanark Brae—a steep hill between the Clyde Valley and Lanark. His horse was making heavy weather of it despite the carter’s not so gentle efforts to ‘encourage’ her up the hill. All of a sudden the poor nag collapsed and died. Her master ran to the cart, pulled out a handful of hay, stuck it in the horse’s mouth and said, “Well, they cannae say ye deeid ‘o hung’ur!1”

Mum told us her father used to get up before dawn and read his Bible by candlelight.

Grandad with me, James and William

When I was three or four, Mum and Dad sent me to the local nursery school. We called it “Miss Francis”. James and William also went there. Miss Francis was both owner and teacher at ‘Beltrees Private Kindergarten’—a house on The Esplanade, just around the corner from Bentinck Street. To reach the school, you entered a gate and walked up a long narrow lane with a hedge on one side and a wall on the other. The basement rooms were the schoolrooms and Miss Francis’ living quarters were upstairs. She was a diminutive woman with brown hair, intelligent eyes, a gravelly voice and a friendly, smiling face. Her fingers were stained brownish yellow with nicotine. Occasionally she took a coughing fit—a full-blown, rattling smoker’s cough.

The day at ‘Miss Francis’, began in the playroom, which had French windows opening onto the lawn. Then we went through to the schoolroom where we sat at little wooden desks. Each desk had a lid. Inside was a tin of coloured chalk crayons, a small, lined writing jotter and a drawing notebook with pastel papers interleaved with tissue, so that the chalk didn’t rub off on the facing page. After morning lessons, there was a milk break. The milk came in a crate of half-pint bottles and had silver foil tops. Patricia Rice, one of the older girls, poked a hole in each foil top with Miss Francis’ penknife and pushed a paper straw into each bottle. We ‘sooked’ our milk with gusto and had a short free-play session. During one play time, I sneaked along the corridor between the schoolroom and the back kitchen and helped myself to some biscuits from Miss Francis’ biscuit tin.

After break we sat on the playroom floor around the blackboard, which was mounted on a wooden easel. Every day, Miss Francis told a story, illustrating it with coloured chalk as she went along. I was enthralled. It was the highlight of my day. The stories usually ended when Miss Francis said with a smile, “And they all lived, happily, ever, after.” An ending that never failed to satisfy my simple little mind.

At home, we often played in ‘the hall’, (the entrance hallway of the flat), from which all the other rooms opened. Mum’s brother, Uncle John worked at Hairmyres Hospital in Lanarkshire. He was in charge of the engineering workshop attached to the hospital, where they made prosthetic limbs and mobility aids. He had contracted polio himself when in his late teens, and walked with a pronounced limp, using a calliper on his bad leg as well as a walking stick to enable him to get about. His car was specially adapted with apparatus coming up from the footwell to allow him to operate the clutch and gear lever by hand. Uncle John made a set of three wooden lorries for me and my brothers, with our names painted on the front. We used to sit on the lorries and ride them up and down the hall. For Christmas one year, Dad got two red Triang pedal cars for James and me, which we loved.

On Christmas Eve, Dad and Mum gave each of us a pillowcase to hang over the end of our bed. We were so excited we stayed awake for ages. Before he went to bed, Dad crept into our room wearing a red dressing gown and wellington boots, and a cotton-wool beard on his face. He quietly filled our pillowcases with presents. We pretended to be asleep, but all the time enjoying the thrill of seeing ‘Santa’ arrive. We knew fine it was Dad, but willingly suspended belief to enjoy those magical moments of make-believe. Even though Mum and Dad told us there was really no such person as Santa, they weren’t so rigid in their thinking that they couldn’t see it from a child’s point of view and allow us a bit of harmless fun.

One day I was playing in the kitchen with a sewing pin I’d found lying about. I’m guessing Mum didn’t know I had it or she’d have confiscated it. I inserted it into the space behind the control knob on the washing machine. Suddenly, an electric shock shot through my fingers and arm. I cried out in alarm and Mum said, “Oh, you silly boy! What did you do that for?” It was a valuable learning experience.

During those early years, Dad used to sit James and me, one on each knee, and tell us Bible stories. Jacob and Esau, Gideon and his three hundred men, David and Goliath, were some of our favourites. But the one we asked for more than any, was Samson and the lion! Dad built the suspense to a crescendo by telling it in real time: “I’m going to see my girlfriend, tum te tum… Grrrrr! The lion growled in the long grass… la la la” (Samson humming a tune) “….Grrrr! GRRR!” Then—“RAAAAAHH! The lion jumped out at Samson and the Spirit of God came mightily upon him, he took it by the jaws and tore it apart.” Dad acted it all out, leaning forward with the two of us still on his knees—what excitement! I think Dad enjoyed telling the story just as much as we enjoyed hearing it—which is why it was so memorable.

Mum and Dad wanted the best for their children. They arranged an interview for me at Greenock Academy (the Scottish equivalent of an English Grammar school). There was a small but affordable fee to pay for the privilege, but Dad and Mum thought we were worth it. Mum took me for an interview with Mr Chadwin the Rector2, a diminutive, florid faced man with a brylcreemed wave of black hair swept back over his head. Like all the teachers in those days, he wore a black teacher’s gown. He looked very grand. When he appeared, I whipped off my cap and saluted. Mum had instructed me beforehand. Mr Chadwin took me by the hand with a smile, and led me into his office with Mum. There he showed me a little book with pictures of carrots and other interesting items. I had to draw lines between one thing and another and match them up. Easy! That was the entrance exam. The old Greenock Academy was an austere, Gothic revival Victorian building which was demolished to make way for the James Watt College building (now renamed as ‘West College Scotland’).

Across the road from the old Academy was Ardgowan Primary school. Because the Academy intake was later, I was sent to Ardgowan Primary for the first couple of terms, until old enough to join the Academy. I don’t remember the Ardgowan school teacher, but I remember a girl called Elspeth Edgar who sat at the next desk to mine. She was a happy girl with a big friendly smile. The infant classrooms at Ardgowan were upstairs, as was the school gym. Every week, we trooped along to the gym for ‘Music and Movement’. We did all sorts of creative poses with our bodies to the music. One song we sang as we went round and round in a line behind each other, was, “tipper ipper arper on my shoulder, “tipper ipper arper on my shoulder, “tipper ipper arper on my shoulder, I am the master.” We drummed our hands on the shoulders of the person in front as we sang. What it meant I had no idea, but I enjoyed it immensely!

The boys toilets at Ardgowan were in an un-roofed, open toilet block outside, in a corner of the playground. Ceramic urinals lined the wall. Whenever I went near the toilet block, the overpowering stink of stale urine assailed my nostrils.

I used to prance around the playground as if riding a horse. I had a little song which I sang in the saddle, which went: “one more river and that’s the river of Jordan, one more river, there’s one more river to cross.” It was my own little world and a satisfying way of spending playtime.

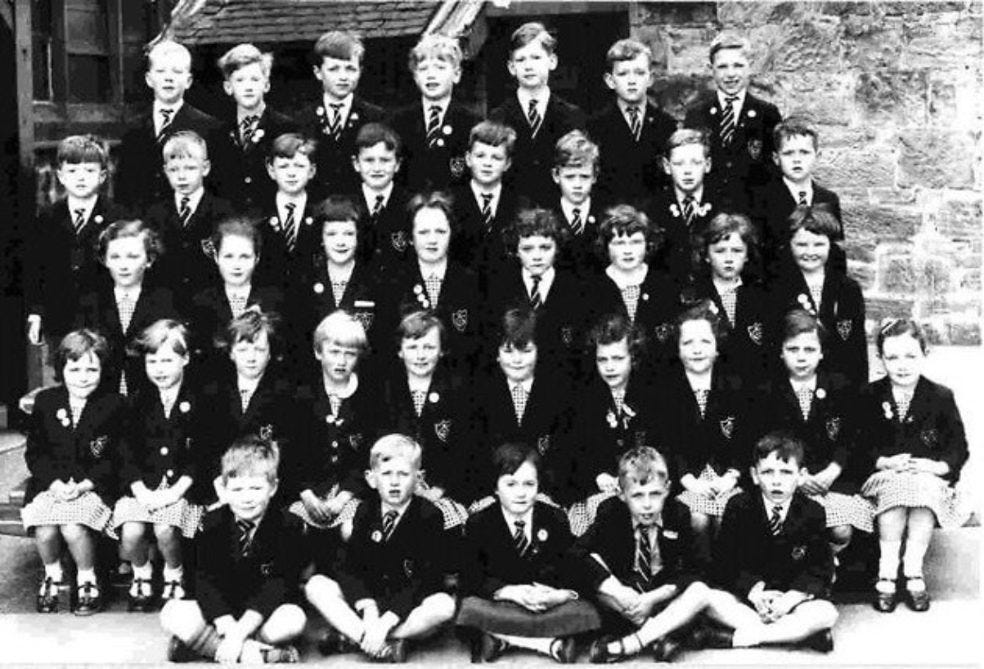

My first teacher in the old Academy ‘Annexe’ building, was Miss McAusland. She was probably nearing retirement age by the time I arrived in her class, but she was an excellent teacher. Gentle but firm. She and her sister lived in the top flat of a house on the corner of Newark Street and Madeira Street, not far from Bentinck Street. In my Primary One class photograph taken at the old Greenock Academy, I’m sitting cross-legged, second from the right in the front row. You can just make out a paper lifeboat badge pinned on the lapel of my blazer.

Primary 1 class photograph at the old Greenock Academy, 1963 or 64 - I’m second from the right in the front row

Here are the names of the classmates in the photograph—as many as my faulty memory can recall—from left to right, starting at the back row and working down:

Back Row (left to right): Donald Mcintyre, Michael Wright, Robin Pollock, Graham McFarlane, William Taggart, Christopher McLean

Second row: Hunter Bowie, Eric Cuthil, Rodger Davies, Kenneth Cochrane, Colin Galbreath, Robin Grant (Titch), Findlay McFee, Stuart McDonald

Third row: Siobhan Kennedy, Helen Osborne, Allison Brown, Moira Taylor, Janice McLaren, Judith Hawkins, Elspeth Edgar

Fourth Row: Christine Hutchieson, Anne McAdam, Morven Lambie, Jennifer Baird, Jacqueline Talent, Lesley Carrick, Jean Carroll, Catriona Stewart, Margaret Henderson, Christine Dunwoody

Front Row: Michael Hall, Brian Hendry, Janice Kennedy, Jo Johnson, Billy Kilpatrick

* * *

I can’t remember if it was in Miss Mcausland’s class or later on in Mrs Russel’s class, but whenever the sun came out, we stopped whatever we were doing and sang:

"Good morning Mr Sun,

Our day has just begun,

We love to see your smiling face,

It fills our hearts with warmth and grace,

Good morning Mr Sun!"

We chanted the last line in unison at the tops of our voices: “GOOD MORNING MR SUN!”

* * *

The Janitor at the old Academy, was a fierce-looking man with a Hitler moustache. He lived in ‘the Janny’s house’ next to the school, the garden of which was separated from the playground by a wooden fence. Known universally as ‘the Janny’, he kept hens in his garden and I often used to look over the wooden fence and watch them clucking and scratching around. I can still smell them in my mind! One boy in my class was Stuart MacDonald. He had glasses and very thin legs. I remember asking him, “How can you run so fast when you have such skinny legs?” William Taggart’s teeth were rotten and his breath smelled like a drain. I stood well back when I spoke with him. I remember him singing the song that was on everyone’s lips in the playground that year, The Beatles song: “She loves you, Yeah, Yeah, Yeah, you know you should be glad…” That must have been 1963 or ’64.

* * *

1 Translation: “No-one will be able to say you died of hunger!”

2 Rector: The old school name for the Head Master or Head Teacher.